I know, slight click bait, but a dodgy hammy can be a real hindrance to you enjoying your sport. I’ve felt the pain, having been on the wrong end of a decent hamstring tear and continuing to push too hard thinking I knew best. Great therapists are typically terrible patients. Or at least that’s what I keep telling myself.

Here’s where I recommend would be a good place to start to get on top of your hamstring niggles. To make things simple, I’ll be talking mostly through my preferred exercises to be included in hamstring rehab through the different stages of injury.

Remember, this blog is general information based on personal experience and my thoughts of where to start. Everyone is different, and every injury is different. It is best practice to seek out a physiotherapist to personally guide your treatment.

Settle Grettle Phase (Day 1-5, or 14 if you’re unlucky)

During the acute phase, there’s a possibility that you will have a small to large tear/multiple tears through the hamstring muscle, musculotendinous junction or tendon to bone insertion or origin. With this in mind, it is imperative you resist the urge to really stretch through the hamstring, and instead, start to get tolerable load through the hamstring early. In my opinion, this helps to promote the “knitting” of the soft tissue for good healing.

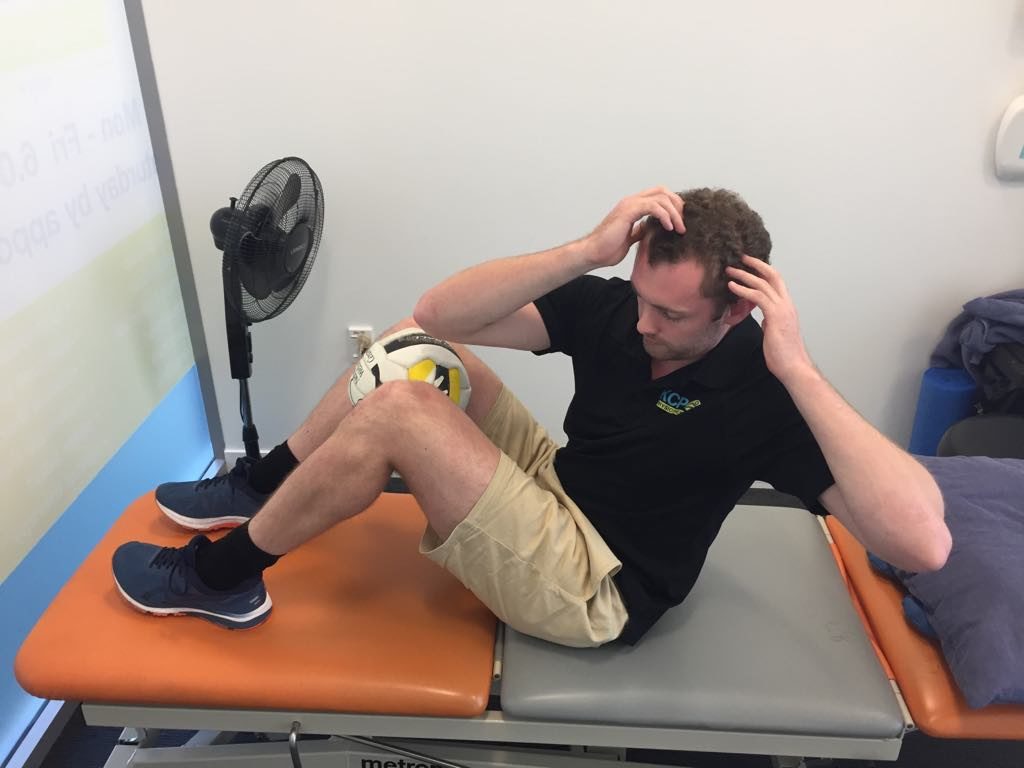

Personally, my favourite exercise is the prone self resisted hamstring holds in the mid-range. Hold for 5-10 seconds against as much resistance you can manage without sharp pain or the hamstring “giving out”. Repeat for 10 repetitions twice daily

The other exercise I like to go with is the double leg bridge. The key being that you lift up as high as you can without the sharp or biting pain. Hold for 5-10 seconds and repeat 10 repetitions twice daily.

You can also get yourself on a stationary bike, adjusting the seat height to make sure that the revolutions don’t feel sharp or biting through the injured hamstring. Aim for 10-15 minutes daily.

Steady load phase (Week 1-6)

At this stage, I would expect the hamstring to be tolerable to light stretching and capable of withstanding progressive loading. Cycling should be pain free, with focus shifting to strengthening through full range before engaging in plyometric or running activity. As we load the hamstring up more, the goal is to complete exercises 3-4 times each week rather than daily as the hamstring will need recovery time to cope with the new demands placed on it. My go-to exercises are as follows:

Outer range isometric loading – a simple progression of the exercise in the acute phase, the difference being positioning the injured hamstring in an area of more length to make the muscle contraction more difficult. Same reps, aiming for 5-10 second holds 10 times.

Bridging on swiss ball (double leg to single leg) – again, building on the other exercise from phase one. Bringing in the swiss ball encourages the hamstring and glute to work harder for stability as well as completing the exercise. Start with double leg holds, progressing to double leg holds with rollouts, before moving to single leg. You can also add a hamstring curl to this exercise if you’re feeling pretty good

Nordic pulses – the beginning of a nordic drop. The idea here is to get the hamstring used to eccentric contractions, a vital component for returning to running (and more specifically sprinting). These exercises are best done with quality rather than quantity, so 4-5 repetitions of 5-10 second holds might be all your hamstring manages before it fatigues. I would recommend only doing “nordic” exercises 2-3 times a week initially as they can cause discomfort initially as you build them into your normal routine.

Hamstring flossing – start to get some sliding action along the hamstring by lying on your back with the affected leg up in the air. Gently straighten your leg out as much as you can manage without any severe pulling/biting/sharp sensations. Steadily work through the reps and you should feel the hamstring start to loosen up.

Hamstrings of doom phase (Week 4-6 and beyond)

Progression to this phase will depend completely on the degree of hamstring injury. Typically though, this is where walking, light jogging and all previous exercises have become painfree and equal (to 90+% of the other side) and there is no pain on palpation through the hamstring muscle. It’s time to WORK.

Full Nordics – you’ll need to lock in your feet, either with a heavy piece of furniture/equipment or utilizing a strong friend to hold your feet down. Keep yourself as upright as possible and slowly lower yourself down to the ground. Hold on for as long as you can, the longer the rep the more benefit you will get out of it. You probably want to aim for 6 good reps and 3 sets the first time you give it a go, steadily building up reps to the 10-12 mark. These are non-negotiable and should be done at least 3 times a week. It’s the only exercise that will make your hamstring muscle fibers longer and stronger at the same time. However, not all good things can last forever, and it can take as little as 3 weeks detraining to see a significant drop in fascicle length at the hamstring. I’ll post the study at the bottom for those interested.

Romanian dead lifts – honestly one of the best exercises for glutes and hamstrings, in my opinion. You can also adapt them to a single leg exercise if you don’t have access to a huge amount of weight. The idea here is we keep the distal insertions of the hamstring at the same length, and increase the length at the proximal origin (the opposite of a nordic). You can use barbell, kettlebell, dumbbell, whatever bell you like. I’d emphasize a slow, eccentric down over a couple of counts before coming up at a regular pace. Keep knees straight, or with a very slight bend, and keep lower back/hips in slight anterior pelvic tilt (keep back flat rather than rounded). Complete slow, high reps on this one for endurance, or low heavy reps for maximal strength.

Seated good mornings – the last of my go-to exercises for hamstrings. A lot like the RDL’s we are changing hip position, but I feel as though shifting the point of load allows you get more of a loaded flossing stretch through the hammy. I’d only usually prescribe this in very slow, high rep ranges (15-20 reps)

Again, there are plenty of ways to rehab your hamstring. It may include rehabbing things that are not the hamstring to get to the root cause of your issue. There are also many more exercises I use on a daily basis with patients in the clinic, but, if you’re looking for a place to start, hopefully this gives you that. It is always best seek out a complete assessment and tailored rehab program for you. If that’s with me, well that’s even better.

Thanks for taking the time to read through my blog, if you have any comments or queries feel free to leave a comment below.

Cheers,

Teej

@theinjuredphysio

Extras for overachievers (unfortunately the first of these articles is not free, but the second one can be found through google scholar):

Alonso-Fernandez, D., Docampo-Blanco, P., & Martinez-Fernandez, J. (2017). Changes in muscle architecture of biceps femoris induced by eccentric strength training with nordic hamstring exercise. Scandinavian Journal Of Medicine & Science In Sports, 28(1), 88-94. doi: 10.1111/sms.12877

Tyler, T., Schmitt, B., Nicholas, S., & McHugh, M. (2017). Rehabilitation After Hamstring-Strain Injury Emphasizing Eccentric Strengthening at Long Muscle Lengths: Results of Long-Term Follow-Up. Journal Of Sport Rehabilitation, 26(2), 131-140. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2015-0099