Last week my boss asked me to write a small piece about sports physiotherapy. I want to share it with you as the task has enabled me to reflect a lot on what I’ve learned and continue to learn doing what I do every day. It has been a big year in growth for me, as I continue to pursue my personal goals and develop towards the health provider I want to be in the future. So here it is!

With an ever growing choice of treatment providers here in New Zealand, sometimes it can be a difficult decision choosing where to go for help. Have no fear, as all the answers you are looking for, are right here.

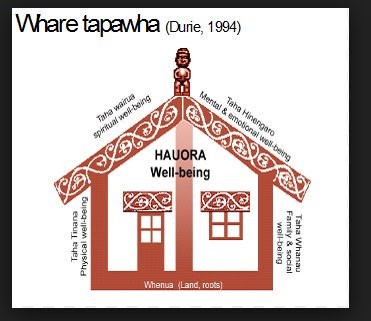

For the average human to enjoy life, we must think of ourselves holistically. High schools and undergraduate university programs up and down the country teach this by incorporating the four pillars of health, our Hau Ora; the physical/taha tinana; the spiritual/taha wairua; the social/taha whanau; and the mental and emotional/taha hingenaro. With this in mind, it is therefore important that whoever you choose has a strong understanding for how all these pillars of health fit.

The sports physio has the upper hand as being involved in sports also requires an in-depth understanding of these four pillars.

The physical goes without saying, as physiotherapists are movement specialists by trade. But it’s not good enough to get people moving, a physio needs to get you moving well. The sports physio needs to have a deeper level of biomechanics, where getting a sports person back performing at the highest level they can becomes a habit of practice. It puts pressure on understanding the injury in its entirety, starting with an accurate diagnosis so the physio can tailor a rehab programme specific to what you need. This means that the sports physio won’t be satisfied with just getting you back to work or running 3 times a week. They will want you to do that effortlessly, so you can enjoy what you are doing.

The spiritual is, by nature, more difficult to see. But athletes have to embody all of who they are to perform at their best and the sports physio knows and respects this. This means that the sports physio will work with your beliefs and cultural needs intimately and incorporate these elements into your rehab programme. It helps to build trust in the physiotherapist, something vital in having the best outcome possible with the rehab plan.

Sport is social. At one stage, most sports physios were sportspeople. The others usually still are. What this means is that they know how important it is to get patients back to regularity as being injured can have a big impact on your social life as well. It’s a common trend to find that a sports physio decided to take up the occupation following a positive experience with their own physio, who helped them return to sport, activity and being able to be around like-minded people.

That just leaves the mental well being. Let me start by saying up front that all activity we engage in has an element of risk that it could do more harm than good. As previously mentioned most sports physios were (or are) avid sportspersons. This means that the sports physio, more often than not, has been exactly where you are. Upset, frustrated, worried, and everything else that comes along with being injured. With this experience comes understanding, not just of what it feels like to be injured, but also what it feels like to lose a part of who you are. Sports is so much more than playing a game once a week. Its socializing with like-minded people, it’s the rush of achieving something challenging, it’s the community that you are a part of when you are tied to a club. Having someone guide you who has been exactly where you are adds an air of reassurance. They’ve been through it, they know there are good days and bad, times of optimism and others of feeling totally defeated. It is all of these elements that make the relationship between a patient and a sports physiotherapist so special.

So, should you ever find yourself injured or unable to complete the things you want to in life, seek out a good sports physio. And tell ‘em I sent ya.

Teej